Does the share of partners from Widening countries affect the success of Twinning project proposals?

27/02/2026

Central and Eastern Europe (EU-13) are gradually strengthening their participation in Horizon Europe. Their share of Framework Programme (FP) funding increased from 6.7% in Horizon 2020 (H2020) to 8.6% in Horizon Europe (HE). Widening plays an important role in this growth; however, the data show that EU-13 convergence towards the EU average and more advanced Member States rests on a broader base. Higher participation by EU-13 is also supported by instruments focused on scientific excellence and human capital (ERC, MSCA), as well as by smaller but fast-growing areas such as Health and Civil Security.

With a touch of metaphor, the convergence of EU-13 towards EU-14 can be seen as a long motorway journey. Widening acts as the “engine” – it provides power to the participation of EU-13 countries in the programme, significantly strengthens it, and is one of the main drivers of their growth in HE. But the engine alone is not enough to get the EU-13 car to its destination. MSCA and ERC function as the “transmission”: they do not immediately bring the largest volumes of funding, but they build institutional reputation, develop human capital, strengthen scientific quality and credibility, and thereby create the conditions for a more active role in other parts of the FP. The thematic areas of Health and Civil Security can be viewed as the “turbo” — EU-13 are growing fastest here and catching up with EU-14. Key thematic areas such as Digital, Industry & Space; Climate, Energy & Mobility; Food, Bioeconomy & Environment; and the EIC are the main “corridors” of the FP where the largest funding volumes are concentrated and where overall results are decided.

The convergence process is not even across EU-13 countries and will only be sustainable if the growth in their participation gradually carries over into open, competitive consortium calls — especially in Climate, Energy & Mobility; Digital, Industry & Space; Food, Bioeconomy & Environment; and EIC/FET. Only then can EU-13 approach EU-14 not just in growth rates but also in the overall volume of funding secured.

Europe’s research funding map is changing gradually in HE. The EU-13 — the newer Member States — improved their position between H2020 and HE: their share of funding rose by roughly 1.9 percentage points (from 6.7% to 8.6%), which corresponds to a relative increase of 28%.

When assessing funding shares, it is important to note that personnel costs (part of every project budget) are significantly lower in EU-13 than in EU-14 countries. The same level of project participation can therefore yield lower financial volumes for EU-13 teams and researchers. Financial indicators thus systematically understate the real level of EU-13 participation and contribution. Even a relatively small increase in funding share (e.g., by two percentage points) may in reality be significant and may reflect a genuine shift in EU-13 positioning within the FP.

Table 1 shows changes in national shares between H2020 and HE. Most EU-13 countries recorded an increase in their share of EU funding in HE (HE/H2020 > 1). The strongest gains were in Lithuania (2.39×), Malta (1.80×), Croatia (1.44×), the Czech Republic (1.39×) and Bulgaria (1.33×). This indicates that even smaller countries can markedly improve their position in the new FP, albeit from a low base. The exception is Hungary, whose relative share declined. Conversely, the large Western European economies — Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands — lost a small portion of their share (collectively from about 65.1% to 60.4%). In absolute terms, however, they remain the dominant recipients in HE. These facts point to a gradual convergence between the EU-13 and EU-14 groups.

Table 1: Share of EU FP funding by country in H2020 and HE. The table compares national funding shares across H2020 and HE; the HE/H2020 column is a change index (value > 1 = rising share, < 1 = falling share).

The “convergence” effect should not be overstated. The HE/H2020 index on which it is based expresses the relative change in a country’s share of the total, not the change in absolute funding volume. For some small countries, percentage-point gains are modest, yet the index reads high (e.g., LT 0.18 → 0.42). Most EU-13 countries that improved in HE started from substantially lower shares than EU-14 in H2020. In HE we therefore observe faster growth from a lower base (indices HE/H2020 > 1). Among the largest EU-14 recipients (DE, FR, ES, …), the share of FP funding decreased slightly, but in absolute funding they remain very strong. In other words, a relative decline in share for large countries does not mean they have “lost weight”; they still command a substantial part of the overall funding volume.

The FPs do not have identical structures, which complicates direct comparisons of participation. It is therefore necessary to bridge structural differences. Even so, several parts in both programmes exhibit clear continuity and are suitable for direct comparison (e.g., ERC, MSCA, Research Infrastructures and Widening). Other areas show thematic continuity — for example, between Societal Challenges in H2020 and the clusters in HE. Some parts differ more substantially, a typical case being the SME Instrument in H2020 and its successor, the EIC, in HE. For this analysis we use a harmonised set of thematic areas that enables us to compare funding shares across both programmes despite structural differences. This yields 13 thematic areas listed in Table 2. Their precise scope is defined in the appendix to the previous analysis “Distribution of FP Funding for the Czech Republic across Thematic Areas in H2020 and HE.” (only in Czech)

Table 2 shows how the European Commission’s funding for research projects shifted across main thematic areas between H2020 and HE. The data indicate not only that EU-13 increased their overall share, but also that the structure of their participation changed.

The sharpest increase for EU-13 occurred in Widening, where their share rose from 11.6% in H2020 to 14.1% in HE. This suggests that Widening remains a key “engine” of their FP participation, whereas for EU-14 it is of only marginal significance (about 1.4%). Note that Widening instruments primarily target countries with lower R&I capacity, and all EU-13 are Widening countries. EU-14 can participate in Widening, but — with the exception of Greece and Portugal — only in a limited way. A notable surprise on the EU-13 side is Food, Bioeconomy & Environment, where their share increased to 11.7% in HE, thus exceeding both the EU average (10%) and the EU-14 level (9.8%). In Civil Security, EU-13 also remain above EU-14 (3.2% versus 1.7%), indicating relatively stronger positioning in this area. A positive shift is also visible in Health, where EU-13 raised their share from 5.2% to 8.6%, and in Culture & Inclusive Society, where EU-13 funding rose by 48% in HE compared to H2020. These results suggest that EU-13 can succeed beyond Widening and are gradually gaining weight in the overall FP portfolio. In ERC, the EU-13 share increased from 7.0% to 9.0% across the two FPs — a move in the right direction, although still well below EU-14 (nearly 20%).

By contrast, in core “consortium-based” areas that form the backbone of the FP, EU-13 shares declined between H2020 and HE: in Climate, Energy & Mobility from 20.4% to 17.3% and in Digital, Industry & Space from 17.3% to 14.4%. In both cases, EU-14 maintained higher shares and confirmed their advantage in areas where large funding volumes are decided. A negative trend is also seen in MSCA, where EU-13 fell from 8.8% to 7.2%, while EU-14 hold a slightly higher level (7.8%). This is concerning, as MSCA is a key instrument for developing human capital and access to international collaboration.

Table 2: Funding shares for EU-13 and EU-14 across thematic areas in H2020 and HE.

A simple comparison of shares between H2020 and HE, as summarised in Table 2, offers a useful first picture of where EU-13 countries gained ground and where they lost it. However, these figures have limited explanatory power: comparing shares between H2020 and HE shows the direction of change, but not the actual dynamics of convergence. The reason is straightforward: thematic areas can have different weights in the two programmes. For example, the budgetary importance of the Widening priority in the overall programme was different in H2020 than in HE; therefore, a higher funding share for a country or group in HE does not necessarily mean a real strengthening of participation—it may simply reflect a change in programme structure.

For this reason, it is not sufficient to track raw funding shares alone. To understand the real dynamics of convergence and to distinguish mechanical shifts from genuine improvements in EU-13 participation in the Framework Programme (FP), we need complementary indicators. Convergence has different drivers, which vary across individual countries and country groups. Well-chosen indicators allow us to identify in which thematic areas, and with what intensity (i.e., growth rate), EU-13 countries are catching up with EU-14 or with the EU as a whole. In other words, these indicators help reveal what is propelling convergence and where its true causes lie.

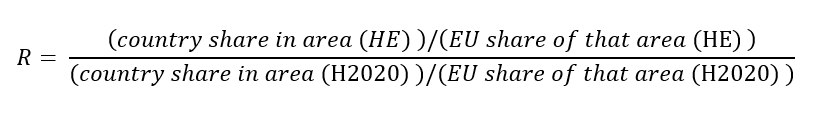

The Dynamics Index (R) shows how a given country moved, in a specific thematic area, relative to the EU average between H2020 and HE. Put differently, it measures whether the country grew faster or slower than the EU average in that area. It does not assess absolute funding volume; it captures the rate of improvement or deterioration compared with the rest of the EU, while also accounting for the fact that the size of individual areas at EU level may have changed between programmes.

We compute it as the ratio of two “normalised” shares: first, take the country’s funding share in the given area in HE and divide it by that area’s share in total EU funding in HE (this removes the effect that the area might be larger or smaller in HE than in H2020). Compute the same normalised share for H2020. R is the quotient of these two:

The formula can be adapted for country groups (e.g., EU-13). Interpretation: R > 1 = improvement relative to the EU (the country/group grew faster than the EU in that area); R < 1 = weakening relative to the EU (grew more slowly than the EU). (Heuristics: R ≥ 1.20 = strong growth; 1.05–1.19 = mild growth; 0.95–1.04 = stable; < 0.95 = decline.)

Because R is relative to the EU and normalised by area size, it neither “rewards” a mechanical expansion of an area in HE nor “penalises” its contraction. It shows the country’s true competitive dynamics in the topic. A quick example: if in H2020 a country had 1.0% of all funds in Health and Health represented 10% of the EU “pie,” its normalised share is 0.10. In HE the country has 1.2% and Health represents 12% of the EU pie; the normalised share is again 0.10. Then R=0.10/0.10=1.0R = 0.10 / 0.10 = 1.0: the relative position is unchanged (even if absolute volume may have grown). By contrast, R=1.20R = 1.20 would mean the country moved 20% above its H2020-era position relative to the EU.

The combined “driver” index T (T = d × R) multiplies the country’s share in a given HE area (d)(d) by the relative growth dynamics (R)(R) between H2020 and HE.

d = the country’s funding share in a specific thematic area in HE (i.e., the percentage of the EU “pie” in that area — size/volume).

R = the Dynamics Index relative to the EU in the same area (R>1 improvement, R<1 deterioration).

Multiplying the two yields T, which is high only when the area is both large for the country (higher dd) and the country is improving relative to the EU (R>1). Thus, T highlights the “drivers” of participation—places where current strength and positive trend accumulate. T is relative to the EU (via R) and weighted by the HE portfolio (via dd). It does not say how much absolute funding a country obtained; rather, it shows where it performs relatively well and where that area plays a substantial role.

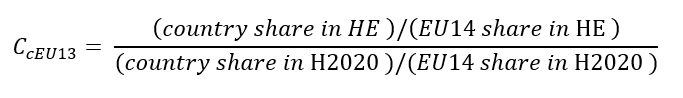

The Convergence Index (C) shows how the relative share of the observed country group (EU-13) changed vis-à-vis the reference—in our case EU-14—between H2020 and HE. In other words, it indicates whether EU-13 moved closer to, or farther from, EU-14 compared to H2020. C > 1 = convergence (catching up); C ≈ 1 = no change; C < 1 = divergence (moving away). It is a direct measure of catching up or falling behind.

For the EU-13 versus EU-14 groups (overall or by thematic area), the formula is:

Analogously, for a single EU-13 country relative to EU-14:

These indicators “level the playing field” across different FP components and reveal where EU-13 growth is driven by increased competitiveness—and where it is more a result of programme-structure changes.

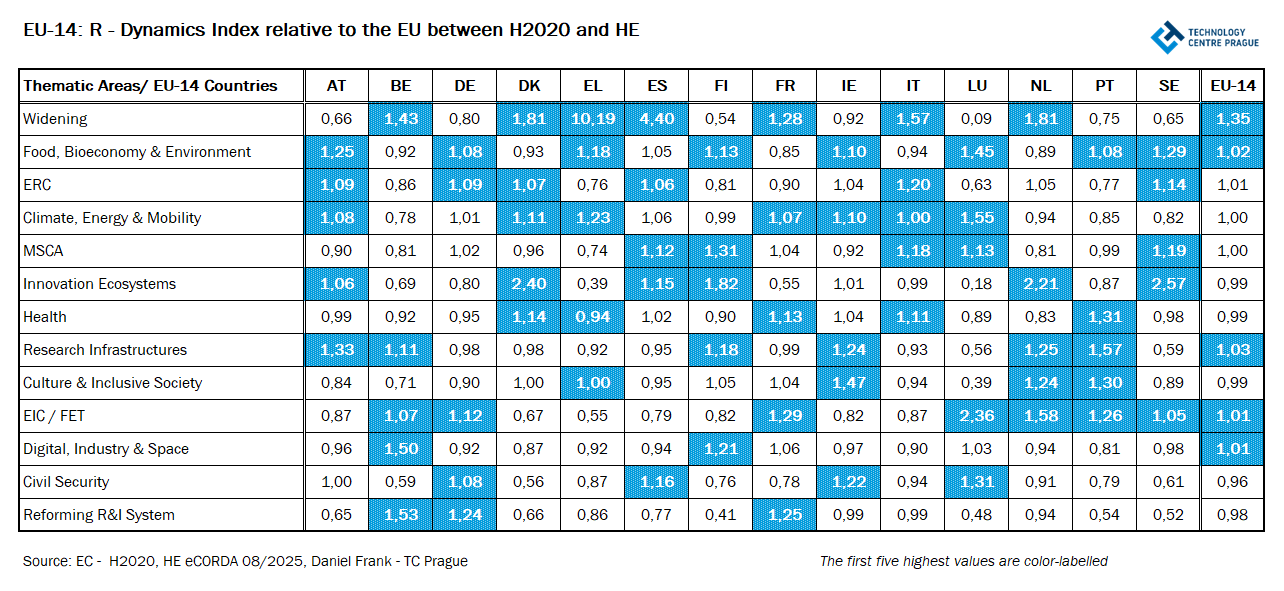

In the main programme areas — Digital, Industry & Space; Food, Bioeconomy & Environment; EIC/FET; and ERC — EU-14 sit very close to R ≈ 1.00–1.02, meaning they grew at roughly the same pace as the EU overall and maintained their position. By contrast, EU-13 grew more slowly in these areas (e.g., Digital ≈ 0.90; Food ≈ 0.81), so while their absolute funding may have risen, it did so more slowly than elsewhere in the EU, and their relative weight edged down.

Conversely, in Health (R ≈ 1.41) and ERC (R ≈ 1.18), EU-13 grew markedly faster than the EU average between H2020 and HE, pointing to improving competitiveness in health and scientific excellence. EU-13 also show above-average dynamics in Civil Security (R ≈ 1.14), while EU-14 slowed slightly there (R ≈ 0.96).

Widening is specific. EU-14 exhibit high dynamics (R ≈ 1.35) from a very low base. EU-13 have R ≈ 0.62 — their absolute funding and share continue to grow, but more slowly relative to EU-14, largely because certain EU-14 countries (notably Greece and Portugal as beneficiaries and coordinators) and institutions from more advanced countries (e.g., Germany) increasingly participate in Widening instruments such as Teaming and Twinning as partner and mentoring organisations supporting excellence development in Widening countries.

Overall, EU-13 converge fastest (in terms of growth rates of their funding share) in Health, ERC and Civil Security, while they lose ground in Research Infrastructures and in technical/consortium-oriented areas such as Digital, Industry & Space and Food, Bioeconomy & Environment.

EU-14, for their part, maintain stable dynamics in the main consortium areas, and their above-average R in Widening is driven by a low starting point and the specific nature of their participation, rather than by a structural shift in favour of EU-14.

Table 3a: Index R in thematic areas – EU-13 (H2020 → HE)

Table 3a: Index R in thematic areas – EU-14 (H2020 → HE)

For EU-14, the centre of gravity in HE remains in the main thematic areas — ERC; Digital, Industry & Space; and Climate, Energy & Mobility. T reaches around 20 for ERC and about 18–18.5 for Digital, Industry & Space and Climate, Energy & Mobility, reflecting the combination of sizeable funding share (d) and stable growth dynamics (R).

While EU-13 still do not reach EU-14 levels in these areas, they are building their own anchors: Climate, Energy & Mobility (T ≈ 16.9) and Digital, Industry & Space (T ≈ 13) already rank among their key drivers in HE. The importance of Health (≈ 12.2) is rising steadily, and ERC (≈ 10.6) is gradually gaining ground as well.

Mid-portfolio for EU-14 is formed mainly by Food, Bioeconomy & Environment and Health (T ~ 10). For EU-13, Food, Bioeconomy & Environment is slightly weaker (≈ 9.4), while Health stands out as a major driver (T ≈ 12.2). In MSCA and EIC/FET, EU-14 show slightly higher T (≈ 7.9 and 6.9) than EU-13 (≈ 6.9 and 5.6).

Widening again stands apart. For EU-13, T ≈ 8.7, i.e. a structurally significant part of their overall HE performance. For EU-14, T is much lower (≈ 1.9), yet R is high — a reflection of very low starting levels and participation often as partners or mentoring institutions in Teaming/Twinning. The high R thus translates into T only to a limited degree.

At the lower end of the portfolio for both groups lie areas with low T. EU-14 retain relatively higher T in Research Infrastructures (≈ 2.57) than EU-13 (≈ 1.50). EU-13, in turn, show higher T in Civil Security (≈ 3.69 vs. 1.52) and Culture & Inclusive Society (≈ 3.96 vs. 2.24). Innovation Ecosystems and Reforming R&I System remain small in volume for both groups and are not significant sources of growth or momentum.

Figure 1: Comparison of thematic areas by volume, growth dynamics (T and R index) and financial share (EU-13 vs. EU-14)

How to read the chart – This bubble chart compares thematic areas across three dimensions simultaneously:

Horizontal axis (T – “driver” index) = how large and simultaneously growing a given area is (combination of financial share (d) and growth rate (R)).

→ The further to the right, the stronger the “driver” of participation.

Vertical axis (R – growth dynamics relative to the EU) = whether EU-13 / EU-14 grow faster or slower than the EU average between H2020 and HE.

→ Above 1 = accelerating and catching up with the EU,

→ Below 1 = slowing down or losing share.

Bubble size = financial share (d).

→ Larger bubble = greater importance of the area in the programme.

Colours: Blue = EU-14, Orange = EU-13

Table 4a: Index T – EU-13

Table 4b: Index T – EU-14

The strongest catch-up of EU-13 towards EU-14 in funding shares occurs in Health, where C reaches 1.43. EU-13’s share rose from roughly 5.2% to 8.6% between H2020 and HE, while EU-14 increased from 8.8% to 10.1%. Strong convergence is also seen in Civil Security (C = 1.19) and in ERC (C = 1.17).

A different picture emerges in Research Infrastructures (C = 0.69) and Food, Bioeconomy & Environment (C = 0.79), where EU-13 lose ground relative to EU-14. In Digital, Industry & Space, C = 0.89 (a mild shift in favour of EU-14), similarly to Innovation Ecosystems (0.93) and EIC/FET (0.93). These are central consortium-oriented areas in which the EU-13/EU-14 gap is closing more slowly.

Widening is again specific. EU-13 still hold the predominant share (rising from ~11.6% to ~14.1%), consistent with the targeting of this priority. Paradoxically, EU-14 grew relatively faster (from ~0.53% to ~1.41%), hence Widening has the lowest convergence index (0.46). This does not signal a weakening of EU-13; rather, it reflects the expanded participation of EU-14 in Widening projects. Greece and Portugal — though part of EU-14 — act as active beneficiaries and coordinators (especially in Twinning and Teaming). At the same time, institutions from advanced countries (e.g., Germany) join as partner or advisory organisations, which further raises the EU-14 share.

Figure 2: Convergence Index (C): change in the ratio of EU-13 to EU-14 financial shares between H2020 and Horizon Europe by thematic area

Convergence of EU-13 towards the performance of EU-14 in the FP is not uniform. The analysis identifies three distinct profiles differing by participation structure, main sources of growth in funding share, and ability to compete in consortium-based calls. There is no one-size-fits-all support instrument for all EU-13; each group requires a different strategic approach.

This profile includes countries whose participation growth in the Framework Programmes relies primarily on the Widening priority. Widening represents one of the largest components of their participation portfolio (it ranks among the main drivers in terms of the T index), and these countries also achieve above-average dynamics in this area (R ≥ 1). They actively use instruments such as Teaming, Twinning or ERA Chairs, which help them secure funding to develop research centres, build research infrastructure, strengthen human capital (talent recruitment, training, know-how transfer) and deepen international partnership networks with excellent institutions from Western Europe.

In contrast, their participation is still more limited in thematic areas that fund open competitive consortium projects (such as Digital, Industry & Space; Climate, Energy & Mobility; EIC/FET; or Food, Bioeconomy & Environment). This limitation appears either in lower participation share (low T) or slower growth (R < 1). In practice, this means that these countries have not yet been able to succeed to a greater extent in excellence-based competitive calls at EU level.

Typical representatives: Croatia (HR), Slovakia (SK)

Borderline / hybrid cases: Malta (MT) and Lithuania (LT) – they have a strong Widening pillar, but also show significant progress in other areas (e.g. Health, EIC, ERC), placing them between this profile and the People & Excellence profile.

Recommendation: For these countries, merely increasing participation in Widening is not sufficient. It is crucial to build “bridges” from Widening towards the main consortium-based areas of the programme (Digital, Industry & Space; Climate, Energy & Mobility; Food, Bioeconomy & Environment; EIC) and to support the transition from partner roles to more frequent leadership and coordination of projects. Without this shift, the growth potential of Widening will be exhausted and the convergence process will stall.

This profile includes countries that are significantly strengthening their performance in priorities focused on scientific excellence and human capital development (ERC and MSCA). In the R index, these countries achieve values above 1, meaning their share is growing faster than the EU average. At the same time, these priorities rank among the main components of their participation according to the T index – combining rapid growth with a substantial financial volume. As a result, these countries enhance their international scientific reputation and improve their position within the European Research Area.

These countries are also beginning to open space for stronger involvement in other thematic areas of the Framework Programme, such as Health, Climate, Energy & Mobility or Digital, Industry & Space, where in some cases we can already observe early signs of growth. This is not yet a widespread trend, but it represents a clear potential for further progression towards consortium-based collaborative calls.

Typical representatives: Czech Republic (CZ), Estonia (EE), Slovenia (SI), Poland (PL)

Borderline / hybrid cases: Malta (MT) and Lithuania (LT) – they combine a strong Widening component with notable strengthening in other areas (e.g. ERC, Health, EIC).

Recommendation: It is essential to strengthen project preparation support (pre-award), develop mentoring, and systematically identify and support talented principal investigators and promising research teams. At the same time, it is crucial to actively connect excellent individuals succeeding in ERC and MSCA with consortium projects, as these two parts of the Framework Programme currently operate almost in isolation, and many researchers perceive them as two separate worlds.

The objective of research and Framework Programme policies should not be only to achieve scientific excellence, but to translate this excellence into higher participation and more frequent project coordination in the main thematic areas. This requires new mechanisms of collaboration, incentives, and support; otherwise, excellence will remain isolated and will not deliver a broader structural impact.

This profile includes countries whose growth in the Framework Programme is most closely linked to thematic pillars, particularly Pillar II (Digital, Industry & Space; Climate, Energy & Mobility) and, to some extent, areas such as EIC or Health. In these areas, they either achieve higher growth rates (R ≥ 1) or hold a greater weight within their own participation portfolio (higher T) than in other parts of the Horizon Europe programme. These countries are not among the overall top performers in the programme and do not have a strong position in Widening or in excellence instruments (ERC/MSCA).

However, it is important to stress that these countries are generally not programme leaders – consortium-based projects represent the most accessible route for their participation in the Framework Programme, as they make less use of other priorities and instruments (e.g. ERC, MSCA or Widening).

The reasons for this orientation vary: some countries lack sufficient research capacity to compete in excellence-based schemes (e.g. Bulgaria), others are not able to fully exploit Widening (Bulgaria, partly Cyprus), some face political or institutional constraints (e.g. Hungary due to EU restrictions), and very small countries encounter the limits of the size of their research system (Cyprus).

As a result, these countries often participate in consortia mainly as partners rather than coordinators, and their growth in these areas frequently stems from a very low baseline. In the data, they may display R > 1, but this does not reflect a strong position – rather a gradual catching-up with more successful countries.

Typical representatives: Bulgaria (BG), Cyprus (CY), Hungary (HU)

Borderline cases (combined profile): Slovenia (SI) and Poland (PL) – these countries already combine consortium participation with elements of excellence (ERC/MSCA), and are therefore moving towards the People & Excellence mix profile.

Recommendation: These countries need to build capacity for project coordination and management, institutional backing, administrative support and infrastructure. The goal is to gradually shift these countries from a partner role towards more active leadership in consortia, while also opening access to Widening and excellence instruments.

EU-13 are demonstrably strengthening in Horizon Europe, and their convergence towards EU-14 is real. Much of the growth to date has been driven by Widening, which boosted participation and helped to make up part of the historical gap. Widening, however, is hitting its limits — its dynamics relative to the EU are declining and it will likely not sustain further catch-up on its own.

A second major source of growth in EU-13 funding shares lies in Health and Civil Security, where EU-13 are growing faster than the rest of the EU. These areas have become important drivers of convergence.

Performance in excellence instruments (ERC, MSCA) is also improving. Although they do not deliver the largest funding volumes, they strengthen institutional capacity and reputation — prerequisites for success in other parts of the FP.

The key challenge lies in the main consortium areas — especially Digital, Industry & Space; Climate, Energy & Mobility; Food, Bioeconomy & Environment; and the EIC — where the largest share of funding is concentrated. Here, EU-14 still hold a dominant position, while EU-13 lag in both funding share and growth rates. For convergence to be sustainable, the increased EU-13 participation must spill over into these core consortium areas. Relying solely on Widening or on partial gains in Health or ERC is not enough; these are important but limited in volume. Real progress will come when EU-13 increase both their share and the growth rate of that share in Digital, Industry & Space; Climate, Energy & Mobility; Food, Bioeconomy & Environment; and EIC — and, above all, when they move from partner roles to more frequent leadership and coordination of projects in these areas.

Author: Daniel Frank, frank@tc.cz, Technology Centre Prague, 16 October 2025

The publication or dissemination of this article (blog) or any of its parts and attachments, in Czech or any other language and in any form, is permitted only with proper attribution of the source and the author in line with standard citation practices. Any modifications or alterations to the article (other than purely formal edits) may only be made with the author’s consent. This text has not undergone language proofreading.

27/02/2026

27/02/2026

27/01/2026