MSCA Correspondence Analysis: from individual mobility to leading networks and programmes

27/01/2026

Gender issues have been part of the FP for many years. Gender issues started to appear as early as FP5 and have been significantly strengthened since 2002, i.e. since the beginning of FP6. In the ongoing Horizon Europe programme, the gender dimension in research is a cross-cutting theme [1]. The theme of gender in Horizon Europe projects and the EU's increased emphasis on gender equality through the Gender Equality Plans are currently resonating among applicants for projects in this FP as well [2].

It is no secret that men are predominantly active in science, research, technology and innovation in the Czech Republic. International comparisons show that the gender equality score in the Czech Republic is relatively low compared to the rest of Europe and the Czech Republic often appears at the tail end of the statistics. For example, She Figures [2,3], published at the end of 2021, can be mentioned from the most recent gender indicators. According to the EIGE (Gender Equality Index), the Czech Republic ranks 22nd in the EU. The Czech Republic performs below average in all categories, including the proportion of women in decision-making positions in research and innovation or in the proportion of authorship of research publications. The She Figures 2021 study states that the Czech Republic is below the European average with regard to gender equality, and that if there have been any improvements, they are only marginal [2]. The analysis and the Government's Gender Equality Strategy 2021-2030 of February 2021 can be mentioned at the national level. This analysis maps gender (in)equality in the Czech Republic. The document itself summarises that the level of gender equality in the Czech Republic is "well below the EU average" [4].The EU's emphasis on gender equality is also reflected in the different parts of the FPs. The ERC Scientific Council has recently adopted its Gender Equality Plan for 2021-2027. The first Plan was already in place in 2008. comparing the statistics for the 7th Framework Programme (FP7) and Horizon 2020 (H2020), the percentage of women applicants - while still lower than men - increased from 25% on average in FP7 to 28% in H2020 [5].

In this context, it will be interesting to compare how the situation has evolved over time at the EU and especially in the Czech Republic. In this brief analysis, we will therefore look at and analyse the gender ratios in ERC project proposals submitted in the EU and the Czech Republic in FP7, H2020 and the first three calls of Horizon Europe. The data covers the period 2007-2021, i.e. a relatively long time period of 15 years. The EC's non-public database - eCorda, which forms the basis for most of the analyses and monitoring of participation in the FP, is used for the analysis. The non-public e-Corda database allows for a very rough gender analysis of prestigious individual grant schemes such as ERC grants and MSCA-IF grants, as it indicates the gender and nationality of the applicants for these grants. Unfortunately, other personal data such as the age of the female and male applicants, which could be used for a more detailed analysis, are not included in this database.

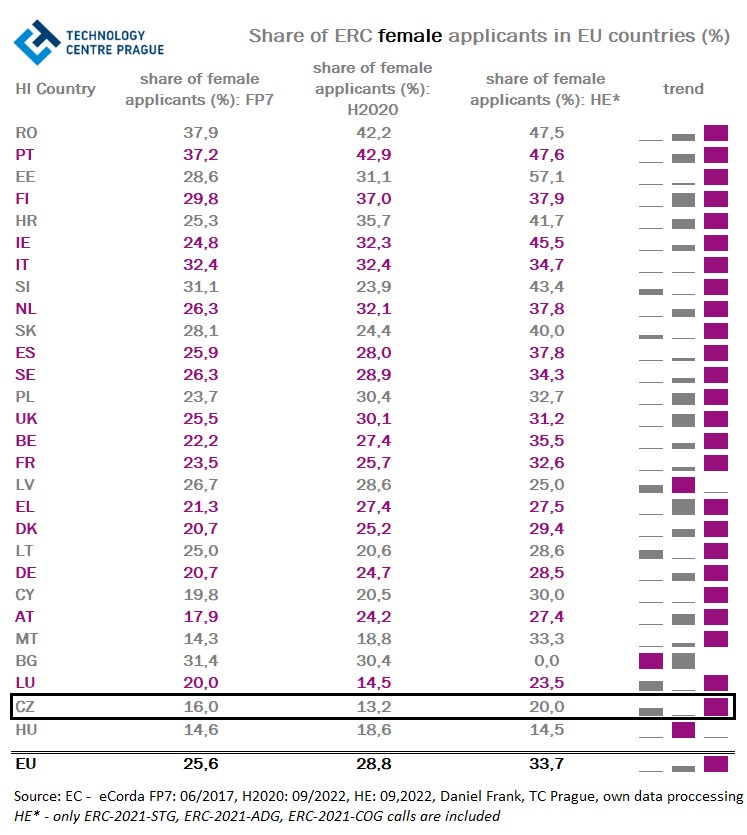

Table 1 presents the EU countries (including the UK) according to their share of women as ERC grant applicants in three consecutive FPs - FP7, H2020 and HE. At first glance, it is clear that the proportion of female ERC applicants at EU level is increasing over time, which is consistent with the analysis carried out by the European Research Council - see above. However, this upward trend does not apply to the Czech Republic, where the share of female ERC grant applicants in the H2020 programme has decreased compared to FP7, although the share of female researchers has increased slightly in the first three calls of the HE programme compared to previous FPs. The level of representation of women among applicants for prestigious ERC grants in the Czech Republic is very low in the long term compared to other EU countries.

Table 1: Share of ERC female applicants in EU countries

The position of the Czech Republic among EU countries in the ERC area de facto follows the position of the Czech Republic in the published gender statistics (see above). The Czech Republic is ranked second to last among EU countries in this indicator. Let us add that the Czech Republic and Hungary have the lowest proportion of women in research of all the countries compared, according to available, incomplete Eurostat data for 2021 [6]. An increasing trend in the proportion of female researchers attempting to obtain prestigious ERC grants can be observed in most EU countries. The ratio of female applicants to male applicants has risen to almost 50 % for Romania and Portugal in the first ERC calls of Horizon Europe. Technologically advanced countries are behind these countries. It should be added that here we are only assessing the activity towards ERC grants, not the quality of the project proposals submitted.

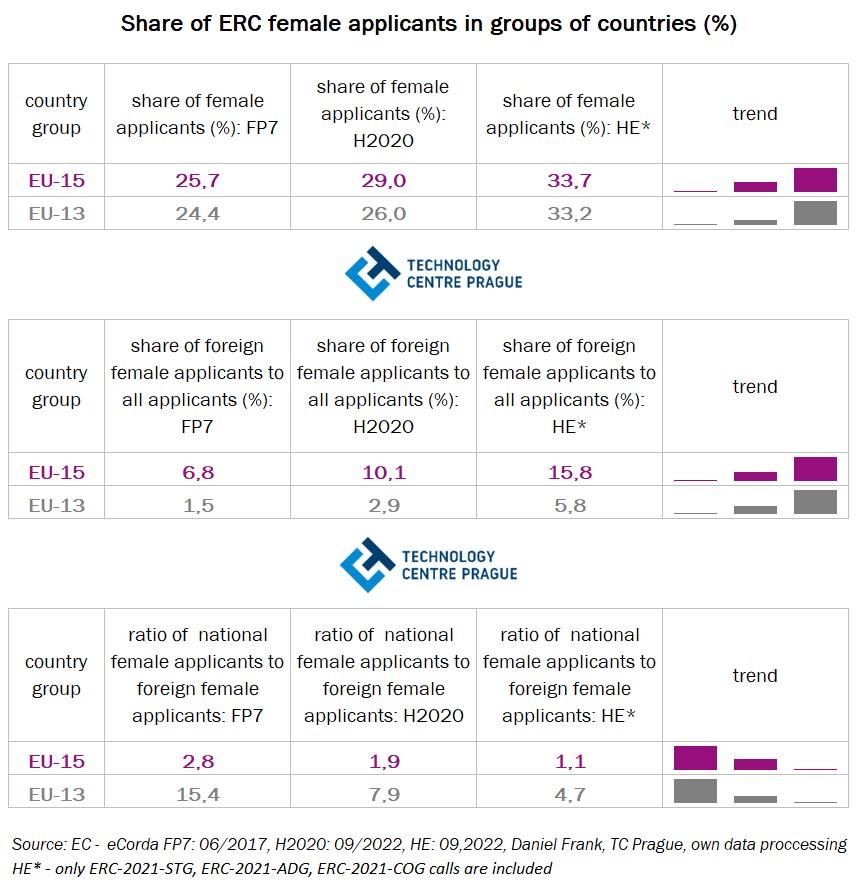

An increasing trend in the share of female ERC applicants across the FPs can also be observed at the level of the EU-15 (including the UK) and EU-13 country groups (see Table 2, upper part). It can be seen that there are no major differences between the EU-15 and EU-13 country groups on this indicator, and the proportion of women applying for ERC grants is almost identical in both country groups across all three FPs. It may be interesting to compare the percentage of foreign female ERC applicants in the host institutions of EU countries. The increasing trend and increasing share from FP7 to Horizon Europe can also be seen here, as well. At the same time, it is noticeable that the share of foreign female researchers as ERC applicants is slightly higher in the EU-15 than in the EU-13, which may be due to the higher scientific prestige of the host institutions in the EU-15 (see Table 2, middle part). The ratio of domestic 'national' female ERC applicants to foreign female ERC applicants in the host institutions of both groups of countries can be seen in the third part of Table 2.

There is a difference between the EU-15 and EU-13 groups again. In the host institutions located in the EU-13 countries, mainly domestic female researchers intended to solve an ERC grant, whereas there were relatively few foreign female applicants. For example, the ratio of domestic female ERC applicants to foreign female ERC applicants in host institutions located in EU-13 countries was about 15:1 in FP7, about 8:1 in H2020 and 5:1 at the beginning of Horizon Europe. These ratios show an increase in the research mobility of female ERC applicants over time. The ratio of domestic female ERC grant applicants to foreign female applicants was not as pronounced in the EU-15 (FP7 - 3:1, H2020 - 2:1) and in the first three Horizon Europe calls the ratio of foreign to domestic female researchers is almost 1:1. Let us add that the ratio of domestic male applicants to foreign male applicants is as follows: EU-15: FP7 3:1, H2020 - 2:1, HE - 1:1, EU-13: FP7 11:1, H2020 - 5:1, HE 3.5:1). The fact that research mobility is increasing over time is also true here, but it is more evident in the EU-15, where there are more prestigious and higher quality host institutions that attract ERC applicants much more than in the EU-13.

Table 2: Share of ERC female applicants in groups of EU countries

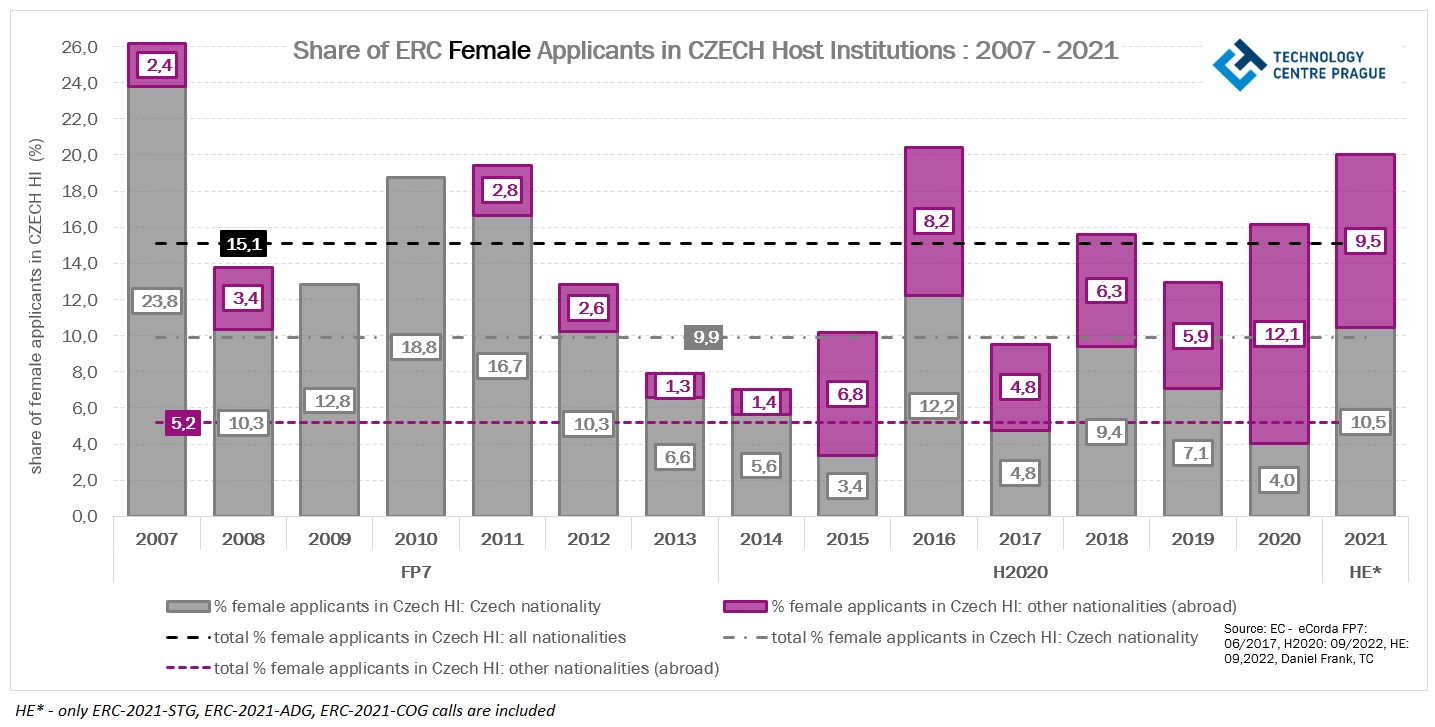

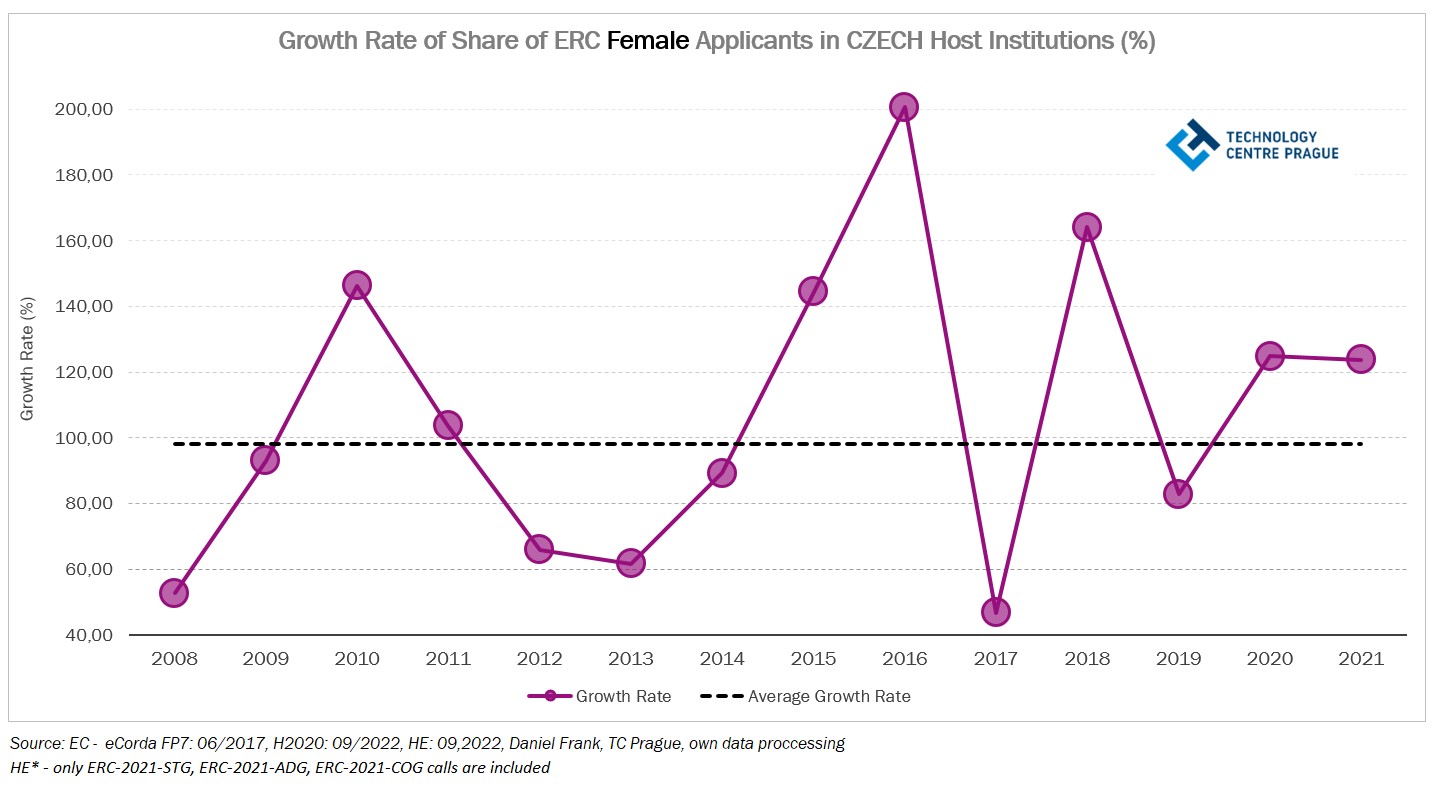

Figure 1 and 2 provide a more detailed view of the trend in the proportion of female ERC grant applicants in Czech host institutions. Figure 1 shows the proportion of female ERC grant applicants (both domestic and foreign) in each year of the FPs. The bars in Figure 1 show the fluctuating trend in the share of female ERC grant applicants in the Czech Republic over time. When calculating the average growth rate of the share of female ERC applicants (Figure 2), we find that the share of female applicants did not change much at the beginning and at the end of the analysed period - i.e. the share of female ERC applicants in the CR fluctuates from year to year, but does not increase in the long term, but rather stagnates.

However, it is clear from Figure 1 that the percentage of female applicants for ERC grants potentially solved in the Czech Republic who have a nationality other than Czech is increasing over time. This is in line with the situation in the EU as a whole (see Tables 2 and 3). Thus, it can be said that research mobility in the Czech Republic is also increasing over time. (Note: this also applies to male applicants; the relevant analytical outputs are not presented in this blog for brevity).

Figure 1: Share of ERC female applicants in Czech HI: 2007 – 2021

The purple part of the bars in the graph represents the proportion of foreign female ERC grant applicants.

Figure 2: Growth rate of share of ERC female applicants in Czech HI: 2007 - 2021

The black dashed line represents the average growth rate.

The ERC funds five types of grants. ERC Starting Grants (STGs) for outstanding young researchers between two and seven years after completing their PhD, ERC Consolidator Grants (COGs) for researchers between seven and 12 years after completing their PhD, ERC Advanced Grants (ADGs) for outstanding researchers who are among the world leaders in their field, ERC Synergy Grants (SyG) for groups of two to a maximum of four Principal Investigators working together on ambitious research problems, and Proof-of-Concept ERC Grants (POC), which are only for Principal Investigators of ERC grants to support the exploitation of the results of their research activities and their translation into practice.

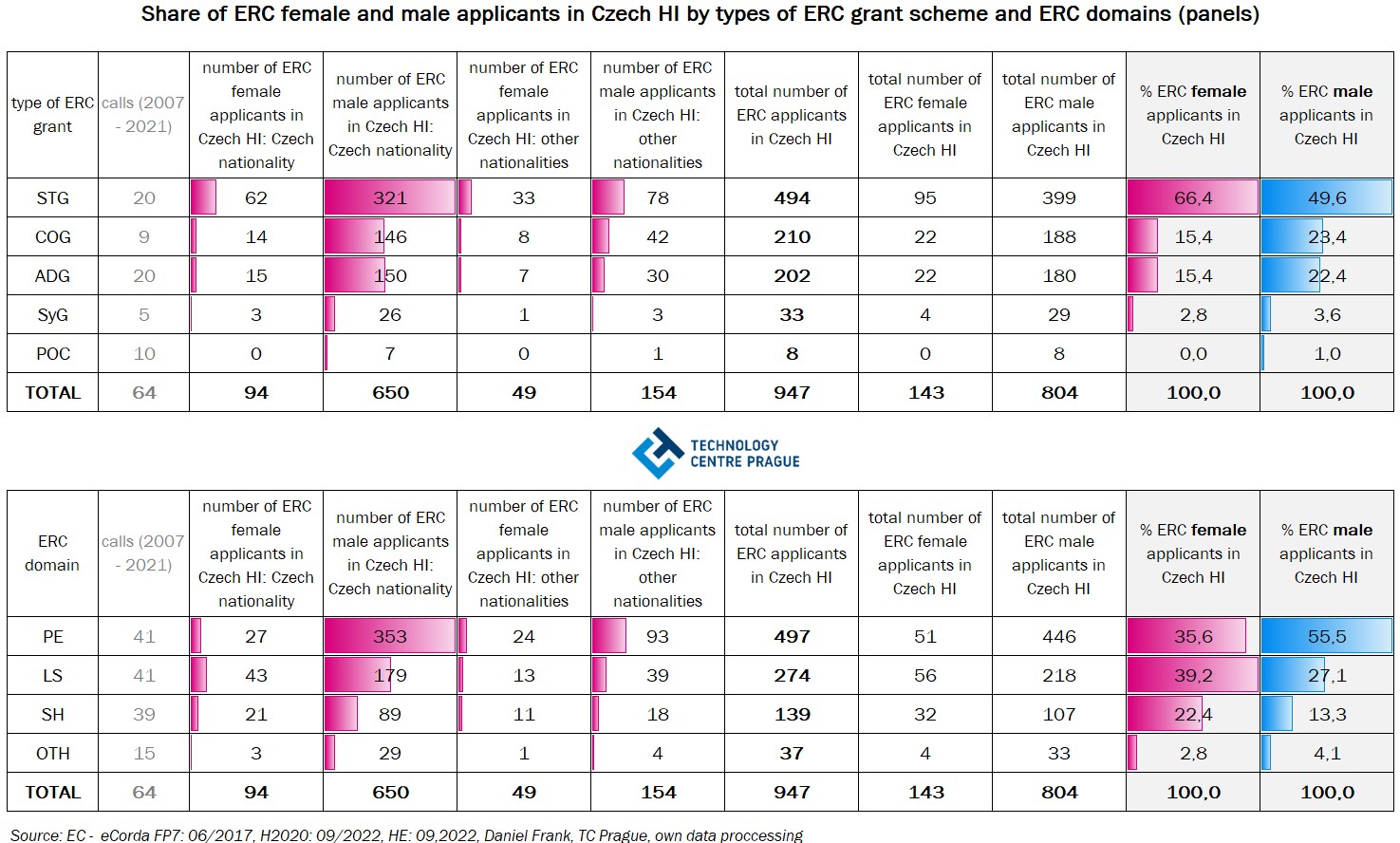

Table 3 shows that more than 2/3 of ERC grant applications authored by female applicants are for young and early-career researchers: ERC-STG, only 15% of project applications were submitted by older experienced female researchers (ERC-ADG). For comparison, project proposals authored by young male researchers (about 50%) were also predominant, with only about 1/4 to 1/5 of project /proposals coming from established male researchers.

Most of the project proposals (STG, ADG, COG) can be classified into three expert sections (domains) after evaluation. These are PE - Physical Sciences and Engineering, SH - Social Sciences and Humanities and LS - Life Sciences. Most of the project proposals submitted by women applicants intending to address an ERC grant in the Czech Republic were included in the expert panels that are part of the Natural Sciences (LS) section - about 39%. More than a third of the project proposals were oriented towards Physical Sciences and Engineering (PE) - about 36%, 1/5 of the proposals were related to Social Sciences and Humanities (SH). In comparison, male ERC grant applicants in the Czech Republic: physical sciences and engineering (PE) - about 56% of the proposals submitted, natural sciences (LS) - about 27% of the project proposals and social sciences and humanities (SH) - about 13%. This comparison shows the difference between female ERC grant applicants and male ERC grant applicants. Female applicants, unlike male applicants, were more likely to succeed in the social sciences and humanities (SH) but also in the natural sciences (LS). Conversely, a lower proportion of project proposals from female ERC applicants is evident in the physical sciences and engineering (PE). See Table 3 for details.

Table 3: Share of female and male ERC grant applicants in HI in the Czech Republic between 2007 and 2021 by type of ERC grant scheme and ERC domain (panels)

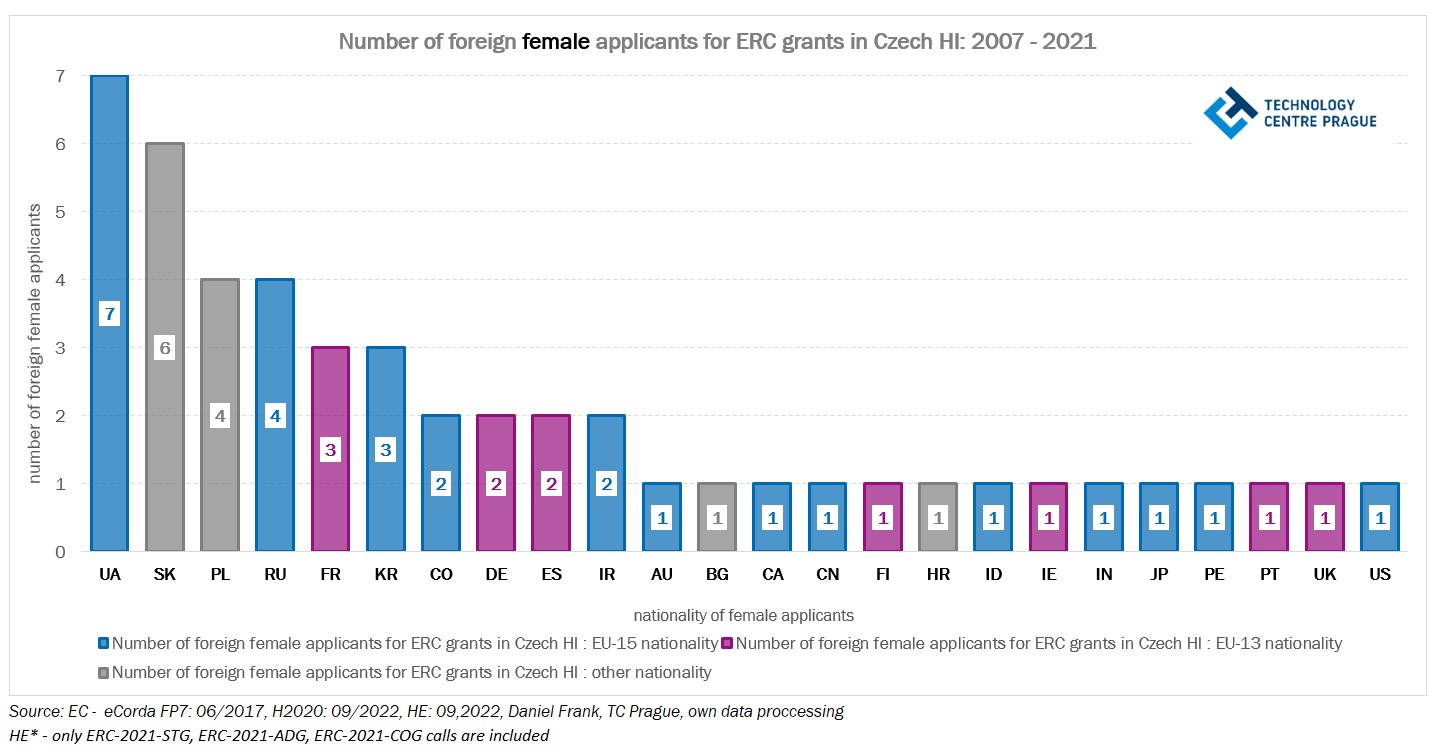

At the end of this brief analysis, it is useful to take a closer look at the national distribution of female ERC grant applicants from abroad who intended to work on an ERC grant through a Czech host institution. 49 female researchers from 24 countries attempted to work on an ERC grant in the Czech Republic between 2007 and 2021. Of this number, about 25% were foreign female applicants from EU-13 countries, about 22% from EU-15 countries or from the Czech Republic including the UK. It is interesting to note that a full 43 % of foreign female applicants came from the four Eastern European countries of Ukraine, Slovakia, Poland and Russia. A more detailed look at the nationality of female ERC applicants is given in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Number of female ERC grant applicants from abroad intending to solve ERC grants in HI in the Czech Republic

According to the information and data presented on the website of the NKC - Gender and Science, Czech research has not been able to give opportunities to qualified women for a long time [7]. According to the European Commission's She Figures 2021 publication, the Czech Republic ranked 44th out of 47 European and other countries surveyed (i.e. fourth from the end) with a 26.6% share of women among researchers. The EU-28 average in 2018 was 33.8% [3, 7]. These facts are naturally reflected in the lower activity of women in the Czech Republic as applicants for ERC grants. NKC - Gender and Science reports that the representation of women among Master's students has been slowly increasing over the last 20 years, as well as at the doctoral level it has a slightly upward trend. However, this situation has no long-term impact on the research situation itself: The biggest drop in the representation of women in the imaginary study-professional pathway is among doctoral graduates and researchers. The representation of women is declining from lecturer to professor. The largest drop in the notional academic career path for women is found among assistant professors and associate professors [7]. The lower representation of women among university academics and the more complex career paths in science seem to be some of the reasons for their low numbers among ERC grant applicants.

Author Daniel Frank, TC Prague, frank@tc.cz

References:

[1] Gender ve vědě a v Horizontu Evropa s Marcelou Linkovou. Informace | Portál Horizont Evropa. [online]. Copyright © 2022 Technologické centrum Praha [cit. 27.11.2022]. Dostupné z: https://www.horizontevropa.cz/cs/mohlo-by-vas-zajimat/nase-sluzby/podcast/informace2

[2] Kašlíková Aneta (2022)., Genderová rovnost je průřezovou evropskou prioritou, Technologické centrum Praha | Časopisy. [online]. Copyright © Technologické centrum Praha [cit. 27.11.2022]. Dostupné z: https://www.tc.cz/cs/publikace/periodika/seznam-periodik/echo/echo-1-2-2022

[3] She Figures 2021 Gender Equality in Research and Innovation: Czechia. Evropská komise, 2021. [online] [cit. 20. 11. 2022]. Dostupné z: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/research_and_innovation/strategy_on_research_and_innovation/documents/ec_rtd_she-figures-2021-country-ficheczechia.pdf

[4] TZ: Vláda dnes schválila Strategii rovnosti žen a mužů na léta 2021 - 2030 | Vláda ČR. Úvodní stránka | Vláda ČR [online]. Dostupné z: https://www.vlada.cz/cz/ppov/rovne-prilezitosti-zen-a-muzu/aktuality/vlada-dnes-schvalila-strategii-rovnosti-zen-a-muzu-na-leta-2021---2030-187164/

[5] https://erc.europa.eu/news-events/magazine/erc-adopts-new-gender-equality-plan

[6] Eurostat - Share of women researchers, all sectors, online data code: TSC00006 last update: 21/10/2022 23:00, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tsc00006/default/table?lang=en

[7] Ženy ve vědě: data | NKC - gender a věda. NKC - gender a věda [online]. Dostupné z: https://genderaveda.cz/zeny-ve-vede/1

27/01/2026

22/12/2025

02/12/2025